NONFICTION

“I’ve Got the Joy” — Christian Music in an Upside-Down Kingdom

The gospel is a story of great inversions, one full of unexpected turns. God becomes man, in a move from wealth to want, beauty to brokenness, eternal embrace to utter rejection — in short, a move from heaven to earth to hell and back again.

Song lyrics can speak about this inversion, or they can portray the inversion itself, embodying its upside-down ethic. Music, as with all the arts, offers a way to refresh our view of beauty, helping us to see differently. As Paul Klee is famously credited with saying, “Art does not render what is visible, but renders visible.”1 Music, in particular, touches us at multiple levels — cognitive, emotional, visceral — to convey truth in ways that mere facts or assertions cannot. I wish to highlight here three contemporary songs that have interpreted afresh for me these great inversions of our Christian faith and creed.

He Rescued Me (Red Mountain Music)

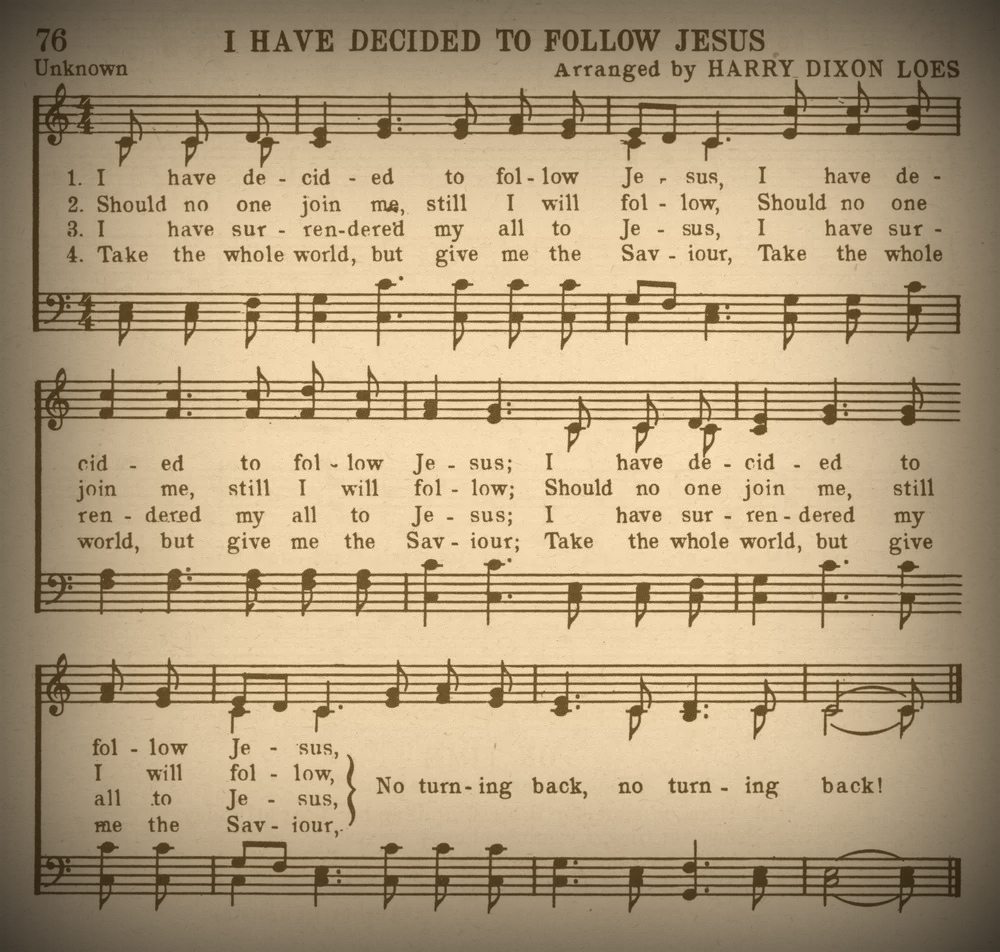

In their piece “He Rescued Me,” the worship music collective Red Mountain Music in Birmingham, Alabama, took the old missionary hymn, “I have decided to follow Jesus,” and did something unexpected with its words.

Instead of its well-worn lyrics, a deeply reverbed woman’s voice sings, “I never wanted to follow Jesus.” She repeats this line three times over, just as in the original version. Against the background of that old, familiar tune, however, that altered line is, at first, shocking. Sung a second time, it is unnerving; by the third time, it takes on a distinctly subversive tone.

ORIGINAL:

I have decided to follow Jesus

I have decided to follow Jesus

I have decided to follow Jesus

No turning back, no turning back.

NEW:

I never wanted to follow Jesus

I never wanted to follow Jesus

I never wanted to follow Jesus

He rescued me, He rescued me.2

Then comes the punchline: “He rescued me, He rescued me.” Subversive, indeed — through just two lyrical lines in total. These words turn the song’s original intent completely on its head. Whereas the original version highlights our agency, these words expose our hubris, questioning whether the decision was ever really ours to make in the first place. It is intended to disrupt our self-understanding, the idea that “I am the master of my fate / I am the captain of my soul.”3 The gospel is truly, even offensively, revolutionary.

At the risk of skirting that age-old soteriological conundrum — whether salvation is wrought by freely-willed human choice, or by God’s sovereignly predestined election — this song subtly draws out a paradoxical truth: that perhaps both aspects are simultaneously true. In this piece, echoes of a bracing personal sentiment, “I have decided,” mingle with another truth we know of ourselves: “I never wanted.” And the complexity of this paradox is further belied by the simplicity of the music. These two mammoth truths are held in tension by words sung across a range of only five notes.

Your Peace Will Make Us One (Audrey Assad)

God’s relationship to power, and His conception of it, are also radically distinct from ours. All through portrayals of His upside-down kingdom, Scripture asserts that the weak and lowly are exalted, the overlooked are given primacy, the marginalized are, in fact, Christ Himself.

One piece that is similarly subversive, in its attunement to these upside-down dynamics, is Audrey Assad’s “Your Peace Will Make Us One,” a reworking of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Originally a Civil War tune set to the words of “John Brown’s Body,” the “Battle Hymn” found new life when paired with a poem that abolitionist Julia Ward Howe was inspired to write for it one evening in 1861, while touring battlefields in Virginia with her husband. The song quickly became a popular marching song for the Union Army, and helped elevate the cause of preserving the Union to greater, loftier, even righteous heights. In her reworking of the piece, however, Assad molds the lyrics into new shape, and the transformation is all the more striking for those familiar with the original words and meaning:

ORIGINAL:

Mine eyes have seen the glory

of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage

where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning

of His terrible swift sword;

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires

of a hundred circling camps;

They have builded Him an altar

in the evening dews and damps;

I can read His righteous sentence

by the dim and flaring lamps,

His day is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies

Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom

that transfigures you and me;

As He died to make men holy,

let us die to make men free!

While God is marching on.

NEW:

Mine eyes have seen the glory

of the coming of the Lord

You are speaking truth to power,

You are laying down our swords

Replanting every vineyard

‘til a brand new wine is poured

Your peace will make us one

I've seen you in our home fires

burning with a quiet light

You are mothering and feeding

in the wee hours of the night

Your gentle love is patient,

You will never fade or tire

Your peace will make us one

In the beauty of the lilies

You were born across the sea

With a glory in your bosom

that is still transfiguring

Dismantling our empires

‘til each one of us is free

Your peace will make us one.4

The original version speaks to a particular vision of God and man, with its call to self-sacrificial service, “Let us die to make men free,” as a fitting response to the grace of a God who “died to make men holy.” Moreover, like Lincoln’s seminal Second Inaugural and Gettysburg addresses, Howe does not presume here to know what side God is on, emphasizing instead His righteous judgment, as God bears “His terrible swift sword.” Christian orthodoxy affirms that God’s Day is indeed “marching on,” and this piece, interpreted rightly, echoes that understanding.

Nevertheless, it should be stated that this same sentiment has, at times, been interpreted in a very different light. Under the banner of Christian nationalism, this song has been used to inspire a sense of vengeance, bloodletting, and retribution, setting Christian discipleship squarely within a paradigm of worldly power. In this framing, strength wins over weakness, “might makes right,” and blood-soaked, nationalistic dominance is understood to be the clear and obvious path to victory. I wonder if it is this triumphalist, nationalistic interpretation of the Battle Hymn that Assad is challenging, stanza by stanza, as she draws attention to dimensions of God’s character that were not a particular focus in the original version.

She writes of “speaking truth to power,” and “laying down our swords,” weaving the robust imagery of restoration, cultivation, and nurturing throughout each line. Whereas the original speaks of “trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored,” the reworked version imagines Christ’s restoring hand “replanting every vineyard ‘til a brand new wine is poured.” Similarly, the second stanza salutes “the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps” in which “His righteous sentence” is accentuated in the firelight of soldiers’ “dim and flaring lamps.” Assad transforms these images into hearth-fires and interprets Jesus in a profoundly tender, maternal light, as one “mothering and feeding in the wee hours of the night.”

Nowhere is this contrast highlighted more clearly than in the final line of each stanza, where the original envisions “God’s truth,” “God’s Day,” even God Himself relentlessly “marching on.” While these are certainly not untrue visions of reality, as we have already noted, Assad chooses to emphasize a different way. Her words evoke Christ’s overpowering greatness through gentleness, echoing the hope woven throughout Scripture (cf. Isaiah 11, John 14, and Ephesians 2) that “Your peace will make us one.”

The writer and poet Shigé Clark, in an essay reflecting on Assad’s version of this “Battle Hymn,” mused: “I wonder how often we go marching into figurative or literal battle on God’s behalf when he would instead call us to gentleness.”5 In fact, the only mention of anything even remotely destructive in Assad’s version is that of “dismantling our empires” in the final stanza. Yet even that seems to be offered in the interest of true and far-reaching freedom. Consider for a moment the seismic shifts in early Christianity, from its roots as a persecuted, breakaway sect of Judaism founded in a backwater colony of Roman occupation, to its elevation as the official religion of the Roman Empire under the fourth-century Emperor Constantine. A mere three centuries, in the scope of history, set the stage for the Church’s relationship with the state, in an often-corrupting alignment with faith and power.

It has been observed that the only time in His life Jesus was ever face-to-face with government leaders, His arms were tied and his face was bloodied. That is perhaps an appropriate model for Christian engagement with state power — even as Lincoln’s posture models another fitting response for those who undertake the awful responsibility of governing. The gospel accounts of Christ’s upside-down kingdom are rife with examples of our Savior eschewing worldly power and esteem in favor of “the kingdom of God,” referenced some 66 times in the New Testament. Even His triumphal Paschal entry, a moment meant to recall great kings riding in on triumphant steeds, was intentionally made on the back of an ass. In so doing, Jesus purposefully made a mockery of this world’s power structures, challenging them over and over throughout His ministry, in ways that even his own disciples failed to recognize at the time.

This subversive “dismantling of empires” takes us even further back, to Genesis 11 and the Tower of Babel, where we see humanity’s efforts to achieve greatness and self-promotion — in short, to “make a name for ourselves” — in order to secure our own self-made peace and prosperity. The creator God, knowing that His creatures can have no true or lasting peace apart from Himself, will have none of it, mercifully undermining our efforts as He confuses and thwarts hubristic attempts at empire-building.

The paradox embedded in this, of course, is that in doing so, we must will our own destruction — relinquishing, rather than clinging to, self-glory — in order to gain even greater life, joy, and flourishing for all. This illustrates a related paradox, presently featured prominently in our public discourse — the difference between “zero-sum” and “abundant” conceptualizations of the world. Only the latter promises freedom for both the oppressed and the oppressor; only the latter is consistent with God’s upside-down kingdom.

Joy (Page CXVI)

Another contemporary female singer-songwriter, Latifah Alattas, demonstrates a similarly subversive take on “I’ve Got the Joy,” a well-known Christian camp song, and flips it completely on its ear.

She wrote the song, “Joy” for her first Page CXVI album, in the immediate wake of her father’s death from cancer. Having watched him draw his last breath earlier that day, she instinctively turned to music to help process the tumult of emotions within her. As she sat at her piano, she found herself asking, “Where is my joy?” Playing minor chord after minor chord, she says she began to perceive a sense of how “joy can be simultaneously felt alongside deep grief, and deep peace …”6

My husband tells the story of an experience during his formative teenage years, when he came across a stack of CDs his sister brought home from her summer job at a Christian bookstore. He popped in one disc after another, getting progressively more frustrated and discouraged by what he describes as “the happy-clappy-Jesus-is-alive” genre that they all seemed to parrot. All of them, that is, except for one CD at the bottom of the pile. Pushing play on that final disc, he was stopped short by the unexpected words of its first track, “What a beautiful piece of heartache this has all turned out to be.”7 Those were the opening lines to “Latter Days” by Over the Rhine, on their 1996 album Good Dog, Bad Dog, and it proved a watershed moment for him, a chance to see how music can possess a level of emotional realism spacious enough for honest grief. Only in that album could my husband locate a piece of his own story and discover Christian music connecting to his own painful experiences of life.

In a similar way, Latifah Alattas’ “Joy” takes the familiar “happy-clappy” lyrics — “I’ve got the joy, joy, joy, joy down in my heart” — but situates them in a minor key, sung with agonizing slowness, such that it seems at first she is mocking the song, leaning sardonically into it, as if an ironic joke:

I’ve got the joy, joy, joy, joy

down in my heart

down in my heart

When the words eventually transition into the next stanza, “And I’m so happy, so happy, so very happy …” a simmering anger begins to build. At first, those words are repeated numbly, over and over again:

And I’m so happy

so happy

so very happy

Gradually, however, a driving undercurrent rises from deep beneath the surface, building to a rip-tide of mourning rage, as the singer cries out in a climax of honest grief:

And I can’t understand

and I can’t pretend

that this will be alright in the end

so I’ll try my best

and lift up my chest

to sing about this … joy, joy, joy8

The bridge culminates in a raw scream that is surely intended to be paradoxical — joy coexisting simultaneously with grief — in the words, “Joy, Joy, Joy.”

She then lands in a place of resolution — though it is no resolution at all, at least not in the typical sense. Having just sung the words, “I don’t understand and I can’t pretend / that it’s going to be okay in the end,” she then transitions to singing the famous words penned by Horatio Spafford, a fellow mourner who poured his own grief into the hymn “It Is Well With My Soul” more than a century earlier:

When peace like a river attendeth my way

when sorrows like sea billows roll

whatever my lot

thou has taught me to say

it is well, it is well, with my soul

The story of Horatio Spafford, who penned the words to “It Is Well,” has been described as “one of the most heartrending stories in the annals of hymnody.” In the span of just two years, from 1871–1873, Spafford suffered first the loss of his entire fortune in the Great Chicago Fire and the death of his only son, followed in short order by the deaths of his four remaining daughters, who were drowned at sea in an ill-fated voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. When going to join his wife, the only member of his family to survive the ship’s sinking, it is said that he wrote the words to that now-famous hymn as the ship he was taking reached the place where his family’s ship was thought to have sunk.9

When we find ourselves grappling with grief in the face of some previously unthinkable loss, joining the lament of a groaning creation, we are faced with a question: Will we offer, even if through gritted teeth, our sacrifice of praise in pain? As Spafford crossed the ocean, I can only imagine what sadness threatened to overwhelm him. When his ship passed over the surface where his daughters lay far below, I wonder if, in some corner of his soul, he hoped for his own ship to bring him to those depths, to deliver him a merciful end to his heartbreak. Perhaps it was out of that dark and sorrowful place that he reckoned with God, wrestling with He who gives and He who takes away — and from that reckoning was born a commitment to still affirm the goodness of God.

This, then, is where Alattas lands. Almost as if returning to an older, wiser mentor, she shifts from the trite music of a children’s camp song, turning instead to a hymn long rooted in Christian tradition. And there, the sacrifice required for her to sing honestly of “joy,” in light of grief’s pain and rage, seems a courageous, upside-down act.

Coda: Music as Paradox

How does one seek, discover, and hold space for deep joy in the midst of profound grief? That vital question goes beyond the scope of this essay, and answering it is arguably the work of a lifetime. Suffice it here simply to note that music both demonstrates and embodies such a paradox in ways that help us see that seemingly disparate truths can coexist. Music is able to express paradox in a way that prose, and even poetry, cannot quite capture, through music’s use of tone, harmony, major or minor chords, and other elements unique to the art form. Against this musical backdrop, upside-down lyrics can elicit deep bodily, cognitive, and creative responses that make it possible to grapple with the paradoxes of being human. Sometimes, it is in fact the musical backdrop itself that speaks most eloquently to our lived realities of grief and beauty, communicating truths too deep to be captured in words alone. That, of course, is itself a profound paradox.

The keen observer will also note that each of these three contemporary songs involves, to some extent, remixing or reformulating traditional hymns. In so doing, these newer versions draw on elements of older works that anchor and provide scaffolding for a process of exploratory reworking. To interpret one’s experience truthfully often involves reworking one’s understanding, sometimes even reformulating or revising former presuppositions, in the hope of landing at a truer, deeper faith. Thoughtful, creative Christian music, such as the three works offered here, gives us a vital gift — the chance to hold space for great paradoxes of our faith, as we celebrate, attest to, wrestle with, and collectively sing truth back to God, gathered in the midst of His people.

- Klee, Paul. “Creative Credo.” 1920. ↩︎

- Red Mountain Church. “He Rescued Me.” Depth of Mercy. Red Mountain Music, 2003. Lyrics of “He Rescued Me” copyright © 2003 by Red Mountain Music, used with permission. ↩︎

- Henley, William Ernest. “Invictus.” ↩︎

- Assad, Audrey. “Your Peace Will Make Us One.” Fortunate Fall Records / Tone Tree Music, 2019. Lyrics of “Your Peace Will Make Us One” copyright © 2019 by Fortunate Fall Records / Tone Tree Music, used with permission. ↩︎

- Clark, Shigé. “Battle Hymn of the body.” The Rabbit Room, 24 December 2021. www.rabbitroom.com/post/battle-hymn-of-the-body. ↩︎

- Garden City. “Alattas Joy in the Midst of Heartache, Tragedy, and Loss.” YouTube, 16 May 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4gOSXPxKSE. ↩︎

- Over the Rhine. “Latter Days.” Good Dog Bad Dog. Scampering Songs Publishing, 1996. Lyrics of “Latter Days” copyright © 1996 by Scampering Songs Publishing, used with permission. ↩︎

- Page CXVI. “Joy.” Hymns. 2009. Lyrics of “Joy” copyright © 2009 by Page CXVI, used with permission. ↩︎

- “History of Hymns: ‘It Is Well With My Soul.’” Discipleship Ministries, The United Methodist Church, 17 Oct. 2019, www.umcdiscipleship.org/resources/history-of-hymns-it-is-well-with-my-soul. ↩︎

Rebecca Martin is a palliative medicine physician with several published works of poetry and narrative non-fiction. Her first book, Though the Darkness, documents her experiences serving for two years in rural Nepal. She and her husband Ryan live in New York’s lower Hudson Valley with their cats, Turtle and Ducky.

Next (Jeremiah Gilbert) >

< Previous (Charolette Winder)

Image: Salvation Songs for Children, Number Four (Pacific Palisades, CA: Int. Child Evangelism Fellowship, 1951).