NONFICTION

Within Five Minutes

On the morning of December 24, 1970, my mother came into my bedroom to awaken me well before I wanted to be awakened. I was seventeen, an age when a boy’s mother can do little right, and she babbled on about having slept on her stomach. This annoyed me greatly because she had interrupted my sleep to tell me how she had slept. I remember saying something along the line of, “Fine—go sleep on your stomach.”

Frustrated by her inability to impress upon me the significance of that activity, she finally said, “Look.”

Realizing this wasn’t going to end until I complied, I sat up, opened my eyes, and directed them toward her.

“Mom, what is it?”

She turned her head from side to side.

“That’s good, Mom,” I mocked. “I can do that, too.”

I mimicked her actions, and she smiled. She had me.

“Don’t you remember my neck?”

Now I was fully awake and without a comeback.

“Oh,” I responded.

“Oh,” she repeated with a triumphant lilt in her voice before leaving the room.

For some reason, people tend to look upward when addressing God, and in that moment, I glanced at the ceiling as I acknowledged what I had been resisting for the last seven months.

“So it’s true,” I confessed aloud.

The entire exchange must have lasted no more than five minutes. Within those five minutes, my universe had changed. Of course I remembered my mother’s neck, and I knew where she had been the previous night.

***

The accident happened on June 21, 1952. My father was in the Army and stationed at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey during the Korean War, and he and my mother were returning from Washington, D. C., where he had been inquiring about the possibility of transferring to Intelligence. They were hurrying to get back to base before his leave expired. It was raining lightly.

Dad saw that the oncoming lane was clear in front of an approaching curve and decided he had time to pass a slower moving car in front of him. Once he was abreast of this car, the other driver sped up. Suddenly, a pale blue car—nearly invisible in the low light of early morning—emerged from the mist.

“I’ll never forget the sight of those headlights coming at me,” I remember my father saying as he was driving the family someplace I no longer remember.

The collision occurred off base, breaking the second cervical (C2) vertebra in my mother’s neck and dislocating it by half an inch relative to the C3 vertebra. I asked Dad how the paramedics had managed to move Mom from the site of the accident to Fort Monmouth Army Hospital without killing or paralyzing her.

“Very carefully,” he answered.

She spent, as she put it, “a long time on a cold, hard table” with sandbags placed around her head. The doctors on base were cautious and initially uncertain as to how to treat her. I don’t know exactly when or how, but they managed to place a Thomas collar around her neck. On July 10, 1952, the Thomas collar was plastered firm, and she was transferred to Saint Albans Naval Hospital on Long Island, New York.

On July 14, her head was shaved, and Crutchfield tongs were applied to her skull. She was placed in traction. No surgical repairs had been made to her neck up to this time. On July 18, she was placed in a modified Minerva cast, still without surgical repair of the injury. Finally, on August 8, she underwent an arthrodesis (bone fusion) of her C1, C2, and C3 vertebrae.

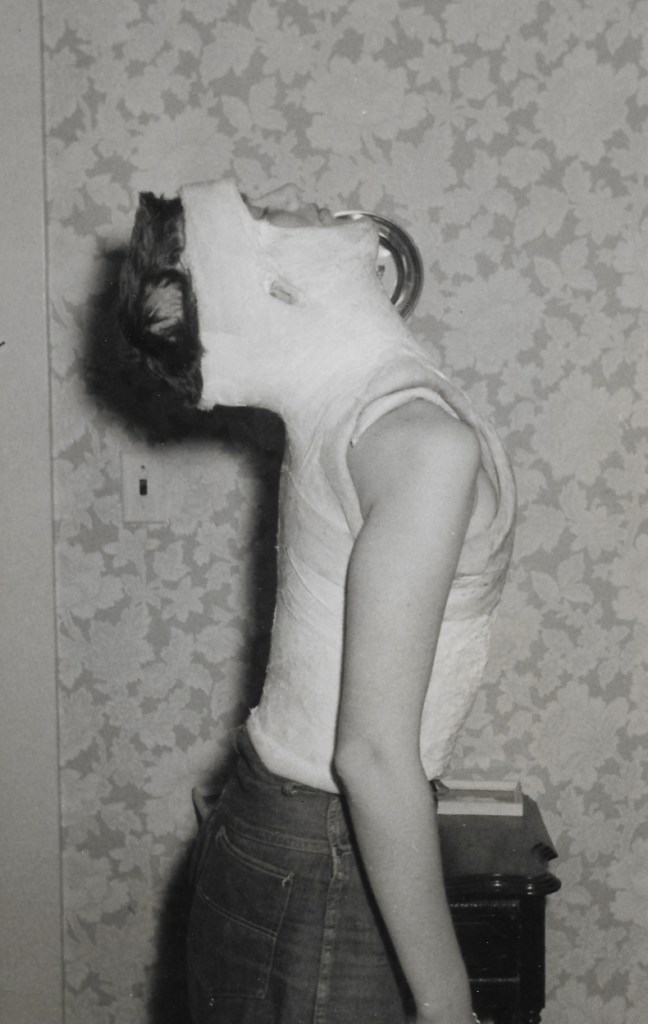

She didn’t remember the exact date they took her off traction, but she sat up for the first time since the accident on August 28, 1952. On September 4, she walked. On September 13, she left the hospital. The cast she was wearing extended from her hips to her forehead with open spaces for her face and ears, and it tilted her head sharply upward. Dad would take her on walks at night so that she could look at the stars and overhanging branches. To avoid the stares of onlookers, my parents didn’t go out in daylight.

On October 9, Mom got a smaller cast that started from above her waist and lowered her head into a somewhat more natural albeit uplifted position. She was able to exchange this cast for a Thomas collar on November 11, 1952. On February 26, 1953, the collar came off for good.

On a sheet of paper torn in half, Mom printed the above litany. From these notes, various conversations with my parents, and a letter my father wrote to his father on June 30, 1952, I have gleaned the information I am now relaying. Reading the time frame gives me chills. My mother spent forty-eight days immobilized by various means with an unrepaired broken neck. That the accident, subsequent transfers, and various manipulations didn’t paralyze or kill her is an extended miracle in itself.

As an ironic footnote to the preceding account, the very accident which threatened my existence also made it possible. The Army granted my father what they termed compassionate relocation, which meant that he was allowed to remain stateside during Mom’s surgery and convalescence while the rest of his unit deployed to Korea. Had he gone with them, he may or may not have survived, but that isn’t the point.

I was born at the base hospital at Fort Monmouth during the summer of 1953, and I wasn’t premature. Doing the math backward from the day of my birth, I have come to the inescapable conclusion that Dad wouldn’t have been present to participate in my conception had he not been allowed to remain with Mom. I count myself uncommonly blessed to be alive.

***

Our middle daughter, now forty, came to visit us for Christmas, and we began going through old footlockers of family memorabilia. On December 26, 2022, we found photographs of my mother at different stages of her convalescence. One, taken in September of 1952, shows a side view of her in the first cast following her release from the hospital. Another shows her in the second cast, and I have a hard time looking away from this one. I’m sixty-nine looking back at my mother when she was twenty-four. She is smiling in this photograph, and her young face displays the radiance of a child.

***

Having taught Biology at the secondary and collegiate levels, I think a brief lesson in anatomy is in order at this point. The C1 vertebra is also called the Atlas vertebra because it supports the skull, and C2 is the Axis vertebra which enables C1 and the skull to pivot atop the rest of the neck. The surgical team which fused the first three vertebrae in my mother’s neck in effect splinted C2 between its adjacent spinal neighbors, thus eliminating two joints. The surgery ended the ongoing risk of paralysis or death, but it also severely restricted the lateral motion of my mother’s head.

***

From the time my brothers and I were young, Mom wore her hair stylishly short, and this allowed us to see a neat, vertical seam over an inch in length on the back of her neck. It wasn’t ugly. It was just different enough to arouse our curiosity. Whenever we asked her what it was, she told us it was the scar from her surgery, and she allowed us to touch it on more than one occasion.

We grew up literally and repeatedly seeing that Mom couldn’t turn her head. Two examples come readily to mind. First, she was an excellent swimmer, a former lifeguard, and a water safety instructor, and while swimming the crawl stroke, she had to lift her head straight out of the water instead of breathing to the side in the normal fashion. Second, whenever she backed the car out of the garage, she had to turn her entire torso in order to see what was happening behind her.

Mom’s condition was a continual part of my upbringing, which I somehow managed to forget while awaking against my will on December 24, 1970.

***

Yes, I knew where my mother had been. She had attended a Bible study and prayer meeting on the night of December 23, 1970. The meeting had taken place out of town, and Mom had arrived home long after I was in bed and asleep. I later asked her to describe what had happened. It was medically impossible on one hand and quite simple on the other.

She told me that people at that meeting had prayed for her, whereupon she had attempted to turn her head but without success. They had prayed for her a second time, and upon repeating the attempt, she had felt something loosen and give way. In retrospect, I understood that the whole point in her saying she had slept on her stomach was that she was able to once she could turn her head.

I also understood that what happened to Mom verified something she had been trying to persuade me to believe since May of 1970. In response to an allergy attack during my track and field season, she had suggested that I ask God to heal me. I had told her that it wasn’t scientific, which was my excuse for not relinquishing that much control, and she had asked me if I believed the stories in the gospels about Jesus performing miracles and healing the sick. Begrudgingly, I had admitted that I did.

“Then why do you think He wouldn’t do that now?” she had followed.

I considered myself an intellectually honest person, and this was a question that continued to bother me after she had raised it. When I saw her demonstrate the evidence of her belief in front of me the following December, I inwardly capitulated. That forgiveness of sin could result in the healing of disease seemed consistent with what I had read in the scriptures, and now I had seen an example of principle becoming reality. I have since learned that this is not always as straightforward or as easy to understand as I would like.

***

During her latter years, my mother told me that recent X-rays of her neck had shown that the bone fusion was still in place, yet our entire family and many friends knew that she could turn her head. In a way, this inexplicable contradiction no longer matters. Mom died of inoperable liver cancer on May 1, 2013, after suffering a number of lesser ailments associated with advancing age. She was eighty-four.

I have no satisfying spiritual interpretation for why she died the way she did, decades after being miraculously healed of a condition that was no longer life-threatening, but that miracle stands as evidence of the greatest theme in her life: faith in a personal God. In Book One of his Summa contra Gentiles, Thomas Aquinas wrote that divine revelation falls into two categories; one is within the reach of our rational capacity, and the other is not. At present, my mother’s story seems to fall into the latter category.

Aquinas also wrote in the same book that truths which exceed our understanding are rightly revealed to us that we might strive after ideals which are above our limited sphere of existence. It is my experience that this effort improves us even when we fall short of attaining those ideals, and here I find the greatest interpretation of Mom being able to turn her head. The phenomenon had a profound effect on our entire family and on many other people besides.

It is February 3, 2023, as I complete the final draft of this account. What I witnessed within five minutes on the morning of a Christmas Eve, just over fifty-two years ago, humbled me and gave me a glimpse into the nature and character of God. It required me to raise my standards of belief and behavior, and it led me from a somewhat detached form of Christianity to faith in a Creator who involves Himself with humanity, both in this life and the life to come.

Robert L. Jones III is Professor Emeritus of Biology at Cottey College. His poems and stories have appeared in Sci Phi Journal, Star*Line, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and previously in Heart of Flesh. He and his wife reside in southwestern Missouri.

Next (Blake Kilgore) >

< Previous (Steve Adelmann)

Photos are courtesy of Robert L. Jones III. All Rights Reserved.